In 2021 Microsoft patented a conversational chatbot designed after a real person to allow users to have virtual conversations with the deceased. At the same time, You Only Virtual was founded as an app that creates the essence of the relationship between you and your loved ones, enabling authentic conversations with the deceased. Their logo, Never Have to Say Goodbye is either a terrifying glimpse of a digital future populated by the restless dead (4) or a more economical method of bereavement therapy.

The death tech company, Eternime is boldly “looking to solve an incredibly challenging problem of humanity.” It’s not biological death that it seeks to cure but the preservation of our digital personas for all eternity. In 2016 James Vlahos created an AI chatbot or Dadbot from conversations with his late father. In 2019, Dadbot became Hereafter AI, a web application that according to the website helps, “preserve meaningful memories about your life and interactively share them with the people you love.” It encourages users to share aspects of their personality, their essence, stories, and memories to create a “virtual you.”

GLIU AI and Visual Arts is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribed

Writing in MIT Technology, Charlotte Jee was given access to a new service, Hereafter AI, and asked if we were ready to talk to our dead loved ones through our communication devices. Hereafter AI’s goal is to let the living communicate with the dead with technology that lets you “talk.” They boast that the digital replica is an authentic representation of the deceased that uses data from interviews while the person is still alive. After their death, those left behind can communicate with their dead loved ones through Alexa, an Amazon Echo device, or an app.

Jee trialed the platform on her still-living mum and dad and their voices lived inside an app on her phone as voice assistants. The California-based company is powered by more than four hours of conversations her parents each had with a real human interviewer. Jee’s parents were asked questions about their lives and memories. In a space of a year, advances in AI and voice technology replaced human interviewers with a bot.

Startups working in the death tech or grief tech industry have created different approaches but similar promises that enable users to talk by video, chat, text, phone, or voice assistance with a digital version of the deceased. Eugenia Kuda founded the Replika chatbot app after her close friend died and was designed to provide valuable conversations of the kind we have with family and friends, therapists, and mentors. The website calls it, “the AI companion who cares.”

Replika and other chatbots were created by inventors who had watched the television episode Be Right Back from the science-fiction drama series, Black Mirror (2013). In it, a woman is bereaved after her husband dies in a car crash and is coerced into using technology that allows her to communicate with an AI that imitates her dead husband, using data from his phone and social networks. Be Right Back connected to tech engineers and the bereaved around the world and pretty soon chatbot services were designed to provide a limited two-way connection to our dead that increasingly impacted how we engage with death, legacy, and remembrance.

The technology to speak to our dead relatives has been reintroduced to consumers by death tech companies like StoryFile and other market-driven startups. I use the term ‘reintroduced’ because similar services have been around for more than a decade but the technology was limited and more importantly, consumers were not ready. For instance, Eternime founder Marius Urschache started his company in 2014 and although it gained a lot of publicity, it failed to ignite the imagination of enough customers to sustain it and by 2018, the company had expired.

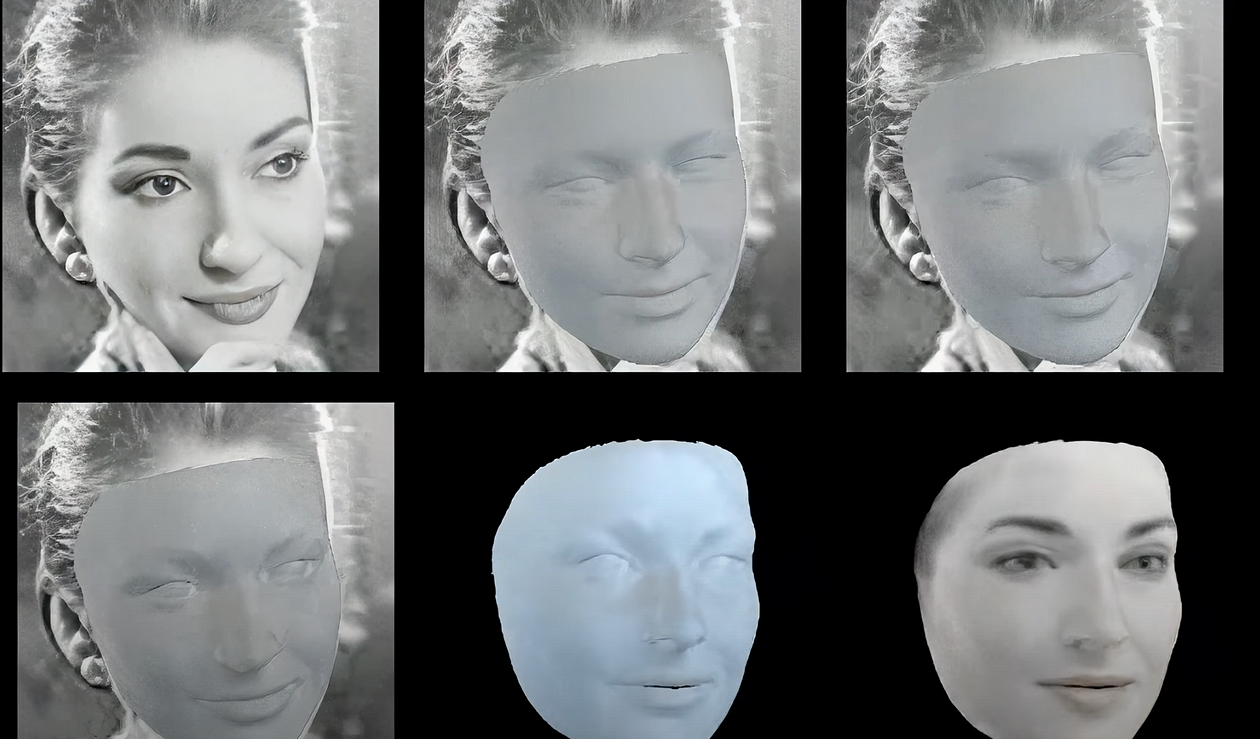

Digital personas have an active or passive presence after death. Passive memorialization is one-way interaction where the dead are silent and the bereaved interact, such as on Facebook Memorial pages. Active presence is two-way interaction such as a conversational avatar or chatbot. The distinction between a live physical person and the dead is becoming increasingly foggy and blurred. Chat-based versions of digital immortality like Hereafter, and StoryFile, help us confront our own mortality and the legacy we leave behind.

Personalized chatbots or voice avatars seek advice and answer questions based on information provided while alive and are no less subjective than an autobiography. We control how we want to be remembered after we die. Interactive internet-based technologies are transforming the way in which we understand death, grieving, and coping with loss. Online communication together with changes in social and religious attitudes (778) in Western society has created a space where the individual is part of the collective.

The societal lockdowns during Covid 19 produced a radical shift in communication that affected traditional death rituals. Saying goodbye to and remembering the recently deceased was conducted on online video streaming platforms. Last August, my ninety-nine-year-old aunt passed away in Southern California. Her extended family resides across the United States and the wider world. For those who could not attend in person, a “Zoom Wake” was organized which included a slide show documenting her ninety-nine years and attendees were given time to say a few words of remembrance.

Technologies’ role in mediating the presence of the dead is embedded in human practices. Right now big companies own your data and survivors have little access to their loved one’s digital archive unless permission was granted prior to death. The death industry is ripe for disruption and Ballater (2015) suggests a reinterpretation of how an economic system perpetuates grief, “it is rather technology’s role as a commodity or means in the production process that is the driving force in shaping the presence of the dead” (Ballater, 2015).

The ethics of creating a virtual version of someone are complex. Who owns the data and what about consent? There’s also a real risk for the recently bereaved that this kind of communication could prolong grief and they could lose their grip on reality. A service that creates a digital replica of someone without their participation raises complex ethical issues regarding consent and privacy. Companies are not obliged to check that users of their services are consensual or in fact, have died.

Feeding the digital afterlife zeitgeist are tech giants who are eager to build a synthetic heaven where big egos go to die. The idea of a synthetic heaven is offensive to many with long-standing religious beliefs even though those same beliefs are as synthetic as digital data. We are living in an AI-powered Matrix future and the richest man in the world agrees. Recently a Twitter user commented that Elon Musk uses the platform to construct a digital replica of our personality in a digital afterlife. Musk responded, “Maybe we’re already in it.” Immortality is not impossible and certainly not for big tech billionaires like Thiel, Bezos, and Musk. Way back in 2012 Paypal founder Peter Thiel stated that “Death is a problem that can be solved.” American data scientist, Emily Gorcenski sees a future where humans will be separated into digital personalities living in computer servers with a labor class maintaining the computers:

“To understand the Metaverse means you have to understand that rich techno nerds genuinely believe they will be able to upload their consciousness before they die.”

The consideration of identity and ethics, the digital afterlife, and immortality are things to consider when creating a digital copy of oneself. Human consciousness or essence transferred to another entity would break continuity, according to Jandric et al, 2018).

According to Heidegger, authenticity is a means to grasp the uniqueness of the individual. Both subject and object are inseparable and reflect Descartes’s notion of a human being as a subjective spectator of objects, with the subject being inseparable from the objective world. He defines authenticity as a means to grasp Dasein or being as unique to human beings in the world. There is a paradox of being singular, independent, and alone while being amongst other people in the world. It is how we fit in and interpret the world around us that makes us unique.

Being developed through the ages and has the character of a technological framework in which humans approach the world in a controlling and dominating way. Being and time address what it means for a human being to exist temporally between birth and death. Being is time and time is finite and ends with our death (Heidegger, 1977, p33–35). With our increasingly technical world, our digital and virtual worlds, Heidegger argues that technical objects are means for an end and are operated by humans but the essence of technology is not anything technological. Technology is a “way of revealing” truth (Heidegger 1977, p12). Reality is not the same in different cultures (Seubold 1986, p35–36). Reality isn’t certain and knowable and true and absolute. It exists in relations. Reality is inaccessible. Technology is a way of revealing a specific way of revealing the world, where humans control reality, production, and manipulation.

Being human is a “relation of being,” we care about how we are perceived in the world around us. This “being in question for oneself” is directed by how we conduct ourselves over our lives. Our being or identity is in constant turmoil while we figure out who we are over multiple lives and identities in relation to ourselves, how to project onto others, and how others perceive us. Understanding of being is about human agency, “being in the world.” We enact roles and characters to cope with the world and what it is to be human.

From the posthumanist perspective, existence and life are embodied. Technology transports the self where the body does not have to be physical or biological but virtual, (Sarah Kember (2003) 2019, p115). Francesca Ferrando suggests that our internet addiction makes physical presence no longer the main space of social interaction. The concept of human has been challenged while posthumanism and transhumanism are philosophical and scientific theories and inquiries (2019, p21). “Technology is pivotal in the strive towards radical life extension and digital immortality; it is also indispensable in re-envisioning life as it is” (2019, p35).

Much of the transhumanism debate is about rethinking the human through technology. Ray Kurzweil is known as the father of the singularity movement which predicts an untethered technological world where technological humans will live forever. “We will continue to have human bodies, but they will become morphable projections of our intelligence…ultimately software-based humans will vastly extend beyond the severe limitations of humans as we know them today,” (2005, p324–325).

According to Kurzweil, the next evolution is technology working alongside humans, not as a replacement but as collaborative partners. “We’re going to become increasingly non-biological to the point where the non-biological dominates and the biological part is not important anymore,” (1999, p35). Kurzweil’s idea of singularity, of a time when memory and consciousness will be uploaded and technologized, also describes the world we are living in now. A world of rapid technological change that has an impact on all sectors of human society and one that is hurtling faster and faster, changing life as we know it forever.

Maggi Saven-Baden and David Burden define digital immortality as an active or passive digital presence of a person after death with two categories of digital immortality. One-way immortality is passive and a read-only presence like Facebook and bots. Two-way immortality is an interactive digital persona. Think of chatbots based on real people or interactive digital personas trained on real people. Replika is an interactive chatbot and is a bit like having a text conversation with a friend. At the other end of the scale is AI technology like StoryFile which use prerecorded videos of the soon-to-be departed, answering questions posed to them by their loved ones, allowing real-time conversations.

The digital afterlife is the idea of a vertical space where data, assets, legacies, and digital remains reside as part of the cyber soul and assumes a digital presence, (Savin-Baden, 2021). Digital grief concepts were developed to make sense of the ways in which digital technology is harnessed to commemorate and memorialize the dead. Digital grief practices are acceptable norms through media and digital media. Kasket (2019) argues that online persistence and the ongoing presence of the data of the dead lead to a more globalized, secularized, and ongoing presence of the dead online on social media and other networks.

Cultural shifts toward restless, posthumous existence and death are in stark contrast to the Victorian image of death as sleep or rest, (Hallam Hockey, 2011). The restless dead online interrupt previous limitations of cemeteries with static headstones and finite biological death. In contrast, digital death is dynamic and interactive, (Savin-Baden, 2021).

Since early 2000, digital bereavement has grown exponentially on social networks and other online communities. Disenfranchised grievers have no social recognition of grief and many people use Facebook to help with loss because they lack the support they need in a society that expects them to get over death and move on. Online networks give validation and a connection with others that would otherwise be absent in the real world.

Alves (2001) argues for the need to examine the impact that the internet and social media are having in the evolution of grief. Practices such as End of Life video conferencing can cause anxiety for those not used to the technology. There is a need to consider the emotional impact of digital afterlife engagement with the bereaved online. Ongoing visibility can be distressing. Alves says it’s vital to create spaces of debate, discussions around death and dying, and an understanding of the values that people place on cyber mourning.

Grief online is continually acknowledged, communicated, and legitimized. Mitchell et al (2012) see online memorials as the driving cause behind prolonged grief. These surrogates for the deceased not only accommodate grief but perpetuate grief, “by enabling the deceased to persist,” (Mitchell et al 2012). And furthermore, “the web affords an ongoing grief that is unhinged partially from longstanding ideas of ‘closure,’ a way of and a separation of the living and the dead,” (Mitchel et al, 2012).

According to Klastrup (2015), there’s a lack of shared norms on social media, resulting in the compartmentalization of death. A death that is no longer shared with a religious vocabulary or belief can’t be vocalized when coping with bereavement, leaving the deceased uncertain about how to grieve properly. Warner (2018) suggests that new norms like mourning online are constantly changing and renegotiated by users of social media.

The traditional hierarchy of the family is usurped by online users. The digital world opens more spaces for mourning and it is difficult to know the true impact on the bereaved because it is often hidden. Walter (2019) argues that there is a need to consider body, spirit, and mourners together, what he calls “the pervasive dead,” which removes the idea of the dead’s separation from living society and instead, “bonds continue and the online dead can appear at any time,” (Walter, 2019, p389).

The purpose of grief is to construct a durable biography that allows survivors to continue to integrate the deceased person into their lives and find a safe place for them, (Walter, 1996). Photographs, videos, social networks, letters, and physical belongings are tangible and intangible vessels of remembrance. After your physical body dies, what legacy will you leave and what will happen to it over time? What tangible and digital traces will you leave behind? For most of us, our lives will be anonymous and forgotten, tossed away in junk stores like tattered Victorian photographs.

We have come to expect the traces of a dead person’s life to settle into fixed spaces and objects. And we assume their legacy, the lessons they passed on, or the example they set as parents will one way or the other come to shape the lives of those they were close to. When someone dies, there’s a risk that their most precious objects will die with them. The very objects are an extension of an individual’s own unique personality. The uniqueness of any given physical object existing in one place and time, with its own fragility, subjected to wear and tear of time makes the bond established with its owner, irreparable. Therefore, the “internal aspect of the object is its storing rather than its object-ness,” (Savin-Baden, 2021).

Those personal objects that do remain after an individual’s death cannot help but preserve the memory of the deceased. For these reasons, death cleaning reaffirms our understanding of the relationship that links life with death because it presents us with the reality of what is left behind after we are gone. Photos, letters, and clothes will exist after we die. The Swedish approach of Death Cleaning prepares us for the inevitable in a calm and rational way. Belongings and keepsakes are put in order and organized to keep those items we want to keep on for posterity, to carry on for future generations, our unique and deep connection with our loved ones’ objects. Does any of this matter once we are dead? There is no guarantee that those who are left behind will hold on to our legacy. And perhaps all that effort and money you put into creating an AI persona will one day end up in a flea market amongst Victorian post-mortem photographs.

According to Heidegger, accepting death tricks the anxiety of our existence because it frees our fear of death. “Anxiety in the face of death is not equal to the fear of death, and it does not indicate a ‘weak’ person on an arbitrary and random event, but as found from the stem existence, existence is open to the fact that they are launched towards the end of existence” (Heidegger, 2014, p324).

Baudrillard saw the shift from stucco angels to computer graphics that reflected changes impacted by culture, economics, and politics. These changes reflected the structure of representation and the gradual loss of the real objective world and its reference. The philosophy of representation, the original, resemblance, and imitation. The classic sign of signifier and signified is the substitution of reality’s image for the real. Nature is the ultimate referent, the Renaissance recreated the natural world, the industrial revolution reproduced the natural world at scale, and the digital world reimagined reproduction. The emblem of resemblance was automation, the mechanical counterpart, the perfect double copy of a person.

Cultural changes in the 17th and 18th centuries led to a “new ideal in the Western world” (Trilley 1972). Humans were thought of as individuals and importance were placed on the individual, which is demonstrated in the emergence of single portraits and autobiographies. The individual is important and demands attention because he or she is an individual. To be human is o be unique distinctive and subsequently an awareness of one’s private unique individuality, and is quite different from the public self (Charles Taylor 1991, Trilling 1972). Therefore, authenticity is understood as being true to oneself. This concept of authenticity led to the development of the self and interiority of one’s life guided by the inner self and thought.

Foucault suggests that the interior life is guided by a religious and psychological culture that looks inward to watch our interior life and tell truths about ourselves, (2001, p58–60). Foucault opposed the idea of a hidden authentic self, referring to the “Californian cult of the self,” (2001, p266) and that the individual must create oneself as a work of art (2001, p392). Instead of finding our true authentic selves, we should create ourselves as a work of art with no rules or tricks “in a process of unending becoming (2001, p49).

The robot is not made in a person’s likeness but in her adjunct. The ambiguity between truth and falsity, reality and appearance from preindustrial simulacrum is replaced by the disappearance of reality through the production and reproduction of systems. The industrial simulacrum is not a counterfeit but a product because the image is fabricated and has no reference to the natural world. In the industrial simulacrum period, signs no longer refer to specific objects but to their meanings. The period also marked the start of serial production. The question of origin has the opportunity of an infinite number of identical objects, objects that are interchangeable and equivalent in market terms. It represents the devaluation from natural law to the market law of value and exchange.

With the shift in representation in the visual arts and in particular, photography as a mode of serial production and reproduction, the photograph was the archetype of industrial simulacrum, creating an infinite number of identical copies, “the increasing circulation of such simulacra in society testifies to reproductions role as the core of industrial capital,” Walter Benjamin (p67).

Baudrillard argued that “we know today that it’s on the level of reproduction — fashion, media, publicity, information, and communication networks-on the level of what Marx negligently called the false lot of capital, meaning, in the sphere of simulacra and code, that the total process of capital is knit together,“ Jean Baudrillard (p5). Reality is subservient to the signifier. Reality is produced by the signifier, the models of signification. We move away from the society of production to consumption. The computer machine produces reality according to its codes. The signifier becomes its own referent.

The internet and vast global networks structure the shifting nature of identity and the role images play in a society that is mediated by images online. Baudrillard uses the term, ‘hyperreal’ and references cultural products or media like cinema and advertising. Hyperreal is a representation of reality that can’t be mistaken for a copy or replica or representation, instead, it’s treated as the real thing, as reality. Referring to television in the 20th century, he argues for the falsehood of a fly-on-the-wall American documentary series, The Loud Family (1971), as not true when there are cameras present, we don’t act naturally, we are acting or affected by the cameras around us.

TV is not something that affects the viewer, we affect TV, or in the 21st century, we affect smartphones. Viewers form part of the same structure and DNA. We model ourselves on it and it models itself on us. Baudrillard argues that it is difficult to separate representation from reality because of a consumer society where electronic media maintains the “illusion of an actuality,” Jean Baudrillard, (p56) that keeps us buying and entertained. We are living in a simulation constructed by the media. We accept the object’s authenticity because it resonates with its real or natural equivalent. Filming children playing in a garden is an example. It is a media copy of an original live event, capturing a moment in time to be viewed after the fact on media devices.

In the twentieth-century post-modern period, the signs of reality replace reality and there is a destruction of meaning. These simulated forms generate an unreal real, a real without origin, superficial, surface statues, hyperreal production, and artificial reality. Baudrillard argues that there is no reality left to represent. Simulated forms do not imitate reality in an illusory manner, as opposed to a copy, the double, the mirror which proceeds and formulates the real. In contemporary existence, what we accept as reality is already simulated. Hyperreality is in place of reality.

Truth no longer exists because there is no reference. Simulation is a world beyond truth, reference, and causality, a fake or artificial world without meaning. “It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real” Jean Baudrillard, (p134). Postmodern culture is artificial and we need a sense of reality to recognize the artifice but we have lost all sense of what is real or artificial. There is no distinction between reality and its representation, only the simulacrum.

Frederick Jameson sees this period as the decline of affect and its replacement by effect. Effect surfaces a certain look, clearly artificial, effect a new object world and cultural style, a style invented and reflected off or represented of a new technology and virtual world. Surfaces destroy meaning and destroy value. Baudrillard (p23) argues that it is not possible to know the differences between authentic and inauthentic, original and copy. Reality is constructed by the codes of society, languages, and conventions from history, and self eclipsed by the demise of interiority.

Synthetic creation, simulation, nostalgia, the reinvention of the past, events of fiction, and memories recreated and fabricated are created through signs that have gone before. This distance from the past, what Baudrillard calls, “the fetishism of lost objects,” (p163), is a return to the figurative when object and substance have disappeared.

Walter Benjamin argues that every original has an element that can never be captured, like loved ones, they can never be reproduced. This unique aspect of the original, according to Benjamin, “the whole sphere of authenticity is outside technical and, of course, not only technical reproducibility,” Walter Benjamin (p43). Artificial intelligence is developing to reproduce copies of our loved ones but they haven’t yet succeeded in essence. The original is a unique presence in time and space and will always be in the frozen past like dated fashion, culture, society, and technology.

The photograph is the archetype of industrial simulacrum, an infinite number of identical copies, “the increasing circulation of such simulacra in society testifies to reproductions role as the core of industrial capital,” Walter Benjamin (p67). Reality is subservient to the signifier. Reality is produced by the signifier and the models of signification. We move away from the society of production to consumption. The computer machine produces reality according to its codes. Functionalism, form to content, object to use. The signs of reality come to replace reality, these simulated forms generate an unreal real, a real without origin, superficial, surface statues, hyperreal production, and artificial reality.

For Benjamin, a work of art is understood from its non-autonomy. Myth and religion give the arts an aura of uniqueness. The authority of revelations legitimizes the place of artwork and celebrates the relationship between the divine and the human. In contrast, the modern way of production is a machine that reproduces and multiplies the original into infinity. Technology is a system of delivering and managing information and creating objects that are substitutable and reproducible, with little difference between the original and copy.

“The authenticity of a thing is the quintessence of all that is transmissible in it from its origin on, ranging from its physical duration to the historical testimony relating to it. Since the historical testimony is founded on the physical duration, the former too, is jeopardized by reproduction, in which the physical duration plays no part. And what is really jeopardized when the historical testimony is affected is the authority of the object and the weight it derives from tradition. One might focus on these aspects of the artwork on the concept of the aura, and go on to say, what withers in the age of technological reproducibility of the work of art is the latter’s aura” Walter Benjamin, (p22).

Imagine seeing the original Mona Lisa painting on grand display at the Louvre in Paris and compare your experience with holding a postcard reproduction in your hand. The art looks the same but it isn’t the same because the way it is perceived and viewed is not the same. The original has decades of historians building its value and importance, this affects us too. Compare also seeing the Pyramids in Egypt to seeing a photograph of them in a book. The experience is different. One step further is a 21st-century comparison of being in the presence of your flesh-and-bone mother and comparing her real-life presence to a photograph of her or an AI replica viewed on an app. The aura or meaning that the original conveys through feeling is not the same as viewing a copy. However, technological advances in AI that can replicate and mimic an original, together with the heightened emotional effects of grief and bereavement, can mimic the effects of the original aura.

When I was in my early twenties, I lived and worked at a hostel in Flagstaff, Arizona, where I drove tourists to and from the Grand Canyon. I have trekked up and down the canyon, experienced unbearable heat, and shared the emotional experience of its scale with visitors. The vastness of the blue and purple stoned canyon can not be imagined without being there. It is an existential awareness, a closeness to a divine-like experience. Looking at the photographs I’d produced on 5×7 prints was deflating. The mechanical reproduction couldn’t capture the enormity of the canyon or the physical and emotional experience of being there.

I have seen the Terracotta Army in Xian, China. Large deep pits hold thousands of life-sized clay statues of warriors, horses, chariots, and weapons, which are individually painted so that no statue is identical. The pits are temperature controlled to protect the clay and provide respite to the brutal humidity outside. There is a feeling of insignificance in scale in comparison to the hundreds, thousands of soldiers, and knowing the history behind the army and how it was discovered centuries later, makes the imagination run wild and creates an aura surrounding their production. Fifteen years later, Liverpool’s World Museum exhibited a handful of clay statues. I went along to the sold-out exhibition and came away feeling nothing. I didn’t feel a sense of scale from a photograph of one of the pits or grasp the enormity of the number of clay figures, feel the cool breeze from the temperature-controlled conditions, or hear the echoes of hushed voices that bounced around the pits.

What is my experience being in the presence of my mother in real-life, compared to a photograph of her or an AI replica viewed on an app? How could I produce a faithful copy of myself that would affect those close to me and what is our perception of human agency presented on different communication and representation devices?

Does AI technology help families cope with grief or do they exploit people at their most vulnerable? What happens to our data after we die? Does humanity have a right to post-mortem privacy and dignity so that our avatar can’t be used by third parties? In the physical world, the body has a right to respect and human dignity in death. Is violation of human dignity applied to the digital afterlife of the dead? And what digital traces will be left behind if you do nothing? Accidental immortalization includes your digital footprint on social network sites like Facebook.

Who owns your footprint after you die? Is it big tech companies or the loved ones you’ve left behind? Access and ownership cause unintended consequences that shift societal norms and behaviors in online spaces. Mourning is mediated and managed in different social spaces. Are you prepared for the inevitable and will you take a deletionist or preservationist stance? What is the long-term impact on the bereaved when third parties control technology platforms and your data, make the rules, govern who has access, and how the data is presented? Deletion of the deceased online footprint on social networks and email accounts is seen as a second loss by families, Bassett (2020, p78) and creates a new form of anticipatory grief. Putting too much weight on technology could develop a phantom of personhood that immediate grief could cause.

Ginger Liu is the founder of Ginger Media & Entertainment, a Ph.D. Researcher in artificial intelligence and visual arts media, and an author, journalist, artist, and filmmaker. Listen to the Podcast.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — –

Akinyemi, C. and Hassett, A. (2021). ‘He’s Still There’: How Facebook Facilitates Continuing Bonds With the Deceased. OMEGA — Journal of Death and Dying, p.003022282110486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228211048672.

Barthes, R. (1988). Camera lucida : reflections on photography. New York: The Noonday Press.

Bassett, D. (2015). Who Wants to Live Forever? Living, Dying and Grieving in Our Digital Society.Social Sciences, 4(4), pp.1127–1139. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4041127.

Baudrillard, J. (2010). Simulacra and simulation. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Univ. Of Michigan Press.

Baur, M. (1996). Adorno and Heidegger on Art in the Modern World. Philosophy Today, 40(3), pp.357–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday199640312.

Bell, G. and Gray, J. (2001). Digital immortality. Communications of the ACM, 44(3), pp.28–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/365181.365182.

Benjamin, W. (1972). A Short History of Photography. Screen, 13(1), pp.5–26.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/13.1.5.

Benjamin, W. (2021). Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction. S.L.: Lulu Com.

Beverland, M.B. and Farrelly, F.J. (2010). The Quest for Authenticity in Consumption: Consumers’ Purposive Choice of Authentic Cues to Shape Experienced Outcomes. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), pp.838–856. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/615047.

Burden, D. and Maggi Savin-Baden (2019). Virtual humans. Boca Raton Crc Press.

Deleuze, G. and Krauss, R. (1983). Plato and the Simulacrum. October, 27, p.45.

doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/778495.

Derrida, J. (2017). ARCHIVE FEVER : a freudian impression. S.L.: Univ Of Chicago Press.

Dutton, D. (1994). Authenticity in the Art of Traditional Societies. Pacific Arts, [online] 9/10(9/10), pp.1–9. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23411033.

Ferrando, F. and Rosi Braidotti (2019). Philosophical Posthumanism. London Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Ann Arbor, Michigan Proquest.

Foucault, M. (1987). Death and the Labyrinth. Athlone Press.

Foucault, M. (2009). The order of things : an archaeology of the human sciences. London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. and Smith, S. (1994). The archeology of knowledge. London: Routledge.

Gilles Deleuze, Boundas, C.V., Lester, M. and Stivale, C. (1990). The logic of sense. New York: Columbia University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. Oxford: Blackwell.

Heidegger, M. (1977). The Question Concerning Technology. New York Harpercollins Publishers.

Heidegger, M. and Hofstadter, A. (2013). Poetry, language, thought. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Thought.

Herzfeld, N. (2002). Creating in Our Own Image: Artificial Intelligence and the Image of God. Zygon®, 37(2), pp.303–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/0591-2385.00430.

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, or, The cultural logic of late capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Jee, Charlotte. (2022). Technology that lets us speak to our dead relatives has arrived. Are we ready? MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/10/18/1061320/digital-clones-of-dead-people/

Jean-François Lyotard (1991). The inhuman : reflections on time. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Kasket, E. (2019). All the Ghosts in the Machine: illusions of immortality in the digital age. London: Robinson.

Kastenbaum, R. (1974). Disaster, Death, and Human Ecology. OMEGA — Journal of Death and Dying, 5(1), pp.65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/8h7p-vuyn-4mnx-j27y.

Kember, S. (2003). Cyberfeminism and artificial life. London ; New York: Routledge.

Kurzweil, R. (1999). The age of spiritual machines. London: Phoenix.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The singularity is near : when humans transcend biology. London: Duckworth.

Maccannell, D. (2013). The tourist : a new theory of the leisure class. Berkeley, California: University Of California.

Maggi Savin-Baden (2021). AI for Death and Dying. CRC Press.

Maggi Savin-Baden and Mason-Robbie, V. (2020). Digital Afterlife. CRC Press.

Magnusson, M. (2018). The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning. Simon and Schuster.

Nancy Katherine Hayles (1999). How we became posthuman : virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature and informatics. Chicago: Univ. Of Chicago Press.

Newman, G.E. (2019). The Psychology of Authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), pp.8–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000158.

Paul-Choudhury, S. (2011). Digital legacy: the fate of your online soul. New Scientist, 210(2809), pp.41–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0262-4079(11)60930-5.

Rosi Braidotti (2013). The Posthuman. John Wiley & Sons.

Savin-Baden, D. (2020). VIRTUAL HUMANS : today and tomorrow. S.L.: Crc Press.

Savin-Baden, M. and Burden, D. (2018). Digital Immortality and Virtual Humans. Postdigital Science and Education, 1(1), pp.87–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0007-6.

SOFKA, C.J. (1997). SOCIAL SUPPORT ‘INTERNETWORKS,’ CASKETS FOR SALE, AND MORE: THANATOLOGY AND THE INFORMATION SUPERHIGHWAY. Death Studies, 21(6), pp.553–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/074811897201778.

Stack, G.J. (1973). Kierkegaard: The Self and Ethical Existence. The University of Chicago Press, 83(2), pp.108–125.

Steinhart, E. (2014). Your Digital Afterlives. Springer.

Tagg, J. (2007). The burden of representation : essays on photographies and histories. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, C. (2018). The ethics of authenticity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Trilling, L. (1972). Sincerity and authenticity. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Walter, T. (1996). A new model of grief: Bereavement and biography. Mortality, 1(1), pp.7–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713685822.

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, [online] 26(2), pp.349–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(98)00103-0.

Wolfe, C. (2011). What is posthumanism? Minneapolis, Minn. Univ. Of Minnesota Press.