When my mother was given a few weeks to live, desperation came over me to photograph and video her likeness and capture her essence, that special something that is unique to her. As a photographer and documentary filmmaker, the technical implications of documenting a subject are part intuition and part practical theory, the latter requires the logical mind. But capturing my mother’s essence was a struggle because I was documenting with the heart and with thoughts of losing her forever. She was also in the latter stages of dementia and I didn’t want to document that part of her life.

My mother recognized me as someone who cared for her and she was mostly gracious to me. Her beautiful smile and cheeky expression were essences that dementia would never take away from her. And this is where my PhD interrupts. Ten years ago this might have been a PhD about the essence of portrait photography in the 19th and 20th centuries. But here we are in the middle of a new technological revolution that can perhaps take us one step further to our deceased loved ones than still photographs and videos ever could.

We now have the capability to recreate our deceased with artificial intelligence (AI). Generative AI can recreate the digital likeness and speech of a person and for the first time in humanity, our deceased can communicate with us via a chatbot (griefbot), or animated avatar. Of course, it’s all trickery and wishful thinking because the dead are dead. AI technology recreates traces of our past loved ones and fools us into thinking that it’s a real conversation. Yet, we want to be fooled. Anyone who has recently been bereaved knows that grief is raw and desperate, that we would make a deal with the devil to bring back to life our precious loved ones. And this is where the commercial death tech companies feed from our desperation to maintain continuing bonds, to soothe grief, to remember the dearly departed. In this respect, AI death tech companies are no different from the commercial endeavors of 19th-century portrait photographers selling post-mortem or spirit portraits of the dead to anyone who would pay for them.

However gimmicky it is, there will always be consumers who either love or hate communicating with a replica of their deceased loved ones. Only last week, it was announced that a new film about Edith Piaf is in the works that uses AI to recreate her voice for the voice-over of the animated film. Fans I’ve spoken to have not appreciated this fakery but will still watch the film regardless.

How will talking to our dead affect our mental health?

In 2021, Jaswant Singh Chail told his friend that his purpose was to assassinate Her Majesty the Queen of England. The friend was an AI chatbot he had named, Sarai, which was created on the Replika platform. On Christmas day that year, Chail scaled the perimeter of Windsor Castle, armed with a crossbow, and wandered the grounds before he was arrested. More than five thousand text messages were discovered between Chail and the chatbot Sarai, some were texts encouraging Chail to act out his deed. Chail was sentenced to nine years in prison.

Eric Schwitzgebel is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Riverside, and is concerned that advances in AI technology would make it more difficult to distinguish between who is real or an AI replica, specifically during vulnerable times in our lives like bereavement which can affect our mental health.

If we want, we can draw on text and image and video databases to create a simulacra of the deceased — simulacra that speak similarly to how they actually spoke, employing characteristic ideas and turns of phrase, with voice and video to match. With sufficient technological advances, it might become challenging to reliably distinguish simulacra from the originals, based on text, audio, and video alone.

When does grief become a mental health issue?

The loss of a close family member or friend can cause prolonged grief disorder. If the circumstances are right, prolonged grief can be debilitating or life-threatening. During Covid-19, those already living alone, became more isolated and withdrawn. Working from home became the norm and not just for digital nomads like myself. Schools were closed and suddenly whole families were trapped at home and going out of their minds. Mental health has become a buzz word and rightly so. People of all ages should feel empowered and get the support they need for their fragile minds. But this has caused a mental health crisis which is stretching mental health services.

A study published by the Omega-Journal of Death and Dying found that continuing bonds between the living and the deceased are prevalent in 30–40% of people. I am one of them. There are photographs of my deceased parents on the walls and side tables in my living room and hallway. There isn’t a day I don’t look at these images and every week I say something to them or repeat an unspoken wish that they were still around.

Rise of the Griefbot

Grief tech is changing the way we communicate with our deceased loved ones and how we cope with their passing. Our digital footprint, such as texts, photos, videos, emails, and social media accounts keeps us connected to the people close to us and across the world. AI voice cloning creates digital replicas of a human voice by analyzing and mimicking speech patterns such as accent, tone, and pitch.

One of the biggest influences on the implementation of AI to assist humans in professional fields like therapy has been the language model chatbot. ChatGPT, developed by Open AI is a prominent example and is used for a number of human needs, such as creating outlines, collaborating on content, writing robotic essays, and supporting mental health.

AI industry growth exceeded $40 billion in the US in 2022 and is estimated to reach $1.3 trillion over the next decade. According to a recent report, the Chatbots for Mental Health and Therapy Market will be worth $1.71 Bn by 2031. These offer support, direction, and assistance for mental health issues, including grief. One of the major health issues is the increased frequency of mental disease. It’s estimated that 1 in 4 adults and 1 in 10 children experience mental health issues on a yearly basis. Known players in the mental health and therapy chatbot market are Woebot Health, Wysa, Minstrong Health, and Marigold Health.

Tess is a mental health chatbot that, according to the website, is like a therapist or a coach. It can cheer you up when you’re down, treat anxiety, and provide a number of tools and exercises to support positive mental health. The bot works on emotional algorithms and machine learning to respond to users. Tess uses “adaptive machine learning technology,” to respond and interact with the patient. Tess is just one of the many “robot therapists” that are being put to work on an overstretched health service and used in conjunction with traditional human therapy. The positives for mental health chatbots are that they don’t cost anything and that they are more accessible to people who are unsure about sharing personal problems with a stranger. Traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or talking therapy is ideally suited to chatbots that are available 24/7 and don’t judge.

According to a 2021 national survey by Woebot Health, 22% of adults had used a mental health chatbot. Barriers to mental health care are largely economic and AI chatbots may reduce the need for human therapists, as well as create a wealth and health divide where those from underprivileged backgrounds will have little human support. AI technology is changing so fast research can’t keep up with it. To date, there are still only small study samples for researchers and medical professionals to make decisions on. These small studies also mean that there are still biases in AI data.

In the mental health field, natural language tracking has been found to be accurate at detecting and classifying different mental health problems like grief, depression, and anxiety. After the COVID-19 pandemic caused a global mental health crisis, chatbots could fill the demand for limited resources in mental health support.

ChatGPT and other large language models could create a more realistic chatbot of a dead person but doing so can be another headache in estate planning. When someone dies, their belongings are shared between the family left behind or given away to charity. It’s been five years since my mother died and I am still going through both my parent’s belongings and scanning photographs along the way. It’s taken a long time because of bereavement. Whenever I notice feelings of grief while opening a black bin bag full of the memories of my childhood -the photographs and letters belonging to my parents -the bag closes once again and another year goes by.

Death technology such as AI videos or bots created from traces of our loved ones have to be created by the soon-to-be departed or those left behind and for some commercial enterprises, there’s a monthly fee to store these visual or audio interactive ghosts of our dead. Many of these companies will fail or the technology will become obsolete. Imagine having to transfer all your loved ones’ memories from the future equivalent of a tape recorder to a CD.

Silicon Valley of the Digital Afterlife

Hollywood and Silicon Valley are often at the forefront of cutting-edge technology. Remember when Carrie Fisher was digitally resurrected for Star Wars after her untimely death in 2016? No one at that time was discussing it as a death tech for the masses. Since last year, a number of AI death tech companies have hit the market, many promising to recreate the “essence” of our deceased loved ones.

California-based grief tech startups like StoryFile, Replika, and HereAfter AI provide a number of services that aim to support people with the loss of a loved one. StoryFile introduced interactive video conversations with the deceased, Replika is a companion and supportive chatbot avatar that evolves the more users text it.

It is a growing worldwide AI death tech niche that uses deep learning and large language models to recreate the likeness, speech, and personality of the dead. Conversational AI chatbots help machines interact with humans. Generative AI creates new content using machine learning algorithms and trained data to create videos, animated photographs, speech, and text.

Grief tech platforms offer a hierarchy of subscriptions which can come at a hefty price. This might explain why my free subscription to StroryFile looked like a video nasty from the 1980s and nothing like the William Shatner promotion on their website. The one-time premium offering fee is $499 per year which gives access to higher resolution and longer running time videos of the deceased.

Seance AI is a platform that allows users to create online conversations with the deceased and according to the founder Jarren Rocks, is a service that provides closure for the bereaved and is not intended as a long-term continuing bonds platform. You, Only Virtual’s premise is to never say goodbye to our deceased loved ones. Its founder, Justin Harrison makes the fantastical proposition to eliminate grief entirely. At the same time, the platform’s website states that it aims to reproduce “the authentic essence” of our deceased loved ones. If essence is related to our identity and therefore what it means to be human, eliminating grief does not make us human. Confused?

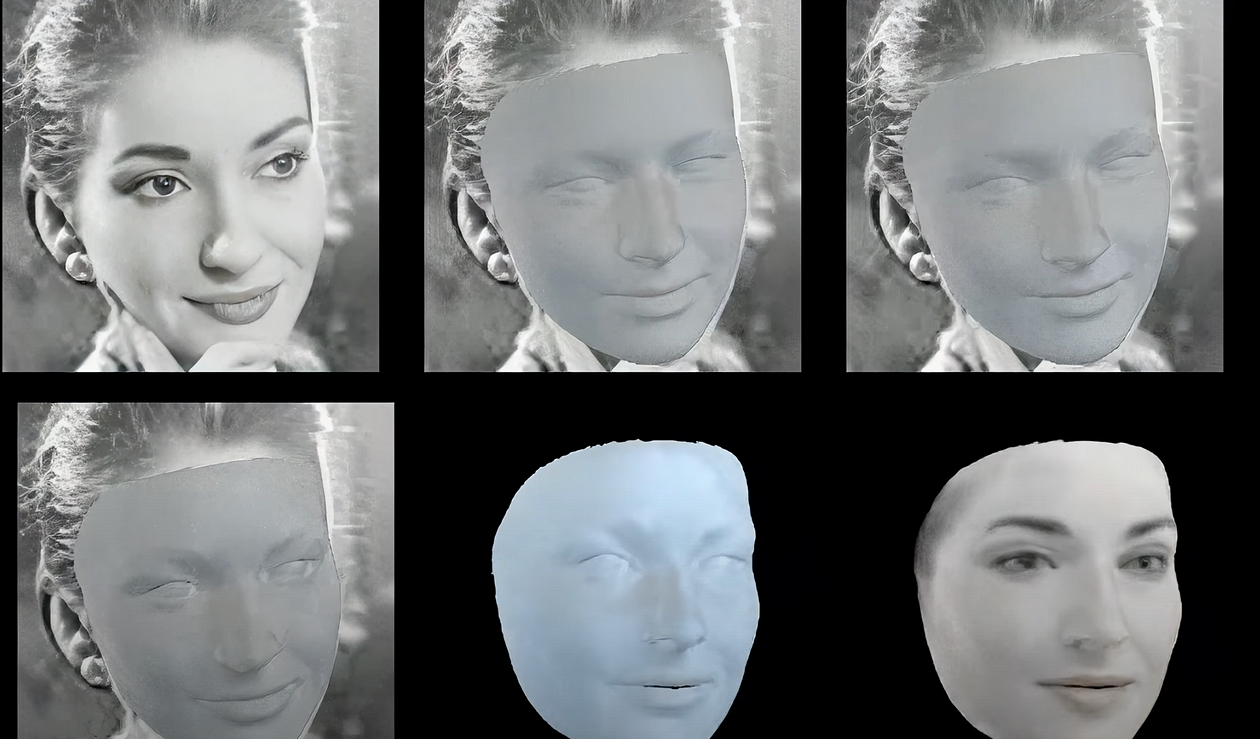

Many of these commercial enterprises use the term “essence.” They insist that the technology can recreate the essence of the deceased. This is where my PhD butts in once again. In my PhD research, I am investigating if AI technology can recreate the essence of a person in the same way or better than a photographic portrait. Essence is a term used by portrait painters and then by portrait photographers from the 19th century to this day. The portrait photographer aims to capture something that represents who the sitter really is. A professional portrait is a performance and capturing the aura of an individual is a setup, a mask. Essence is therefore better suited to describe our loved ones and capturing this in photography is a ritual that is practiced a billion times over. Commercial companies can brag about AI technology replicating the essence of our loved ones. I am questioning their claim to find out if it stacks up. Can AI create the essence of a person better or worse than a still photograph, in the context of the reproduction of the deceased and the technology’s effect on the bereaved?

We have to see commercial grief tech companies for what they are. Customers could be fooled into thinking that they are providing a personal service at a traumatic time in their lives. Stop. They are commercial enterprises. They exist to make money from our needs. I am not saying that all grief tech companies are evil and are solely making money from our grief. They are providing a service that we the consumer have demanded and like photography, we will use it to stay connected to our dead. The technology is new and the relationship with it and its effect on the bereaved is still in research.

There are ongoing legal and ethical concerns surrounding grief tech in relation to consent and data privacy, psychological dependency, bias in datasets, economic access, and technological obsoletion affecting access.

Postmortem deepfakes and deepfake porn are created faster than legislation can attempt to shut them down. New York has mandated regulations for post-mortem publicity rights which are restricted to celebrities. Technology experts are pushing for a “Do not bot me” clause in estate planning. Some states like California and Connecticut have passed data protection policies protecting collected user data by corporations and institutions. The European Union has gone one step further with its General Data Protection Regulation which could have implications for death and grief tech services.

From Silicon Valley to China

China’s AI industry is rapidly advancing and there are a number of companies creating griefbots. Super Brain is designed for the bereaved. Services include visual and audio clips and conversational video-enabled chatbots that mimic the deceased. They aren’t cheap. Customized griefbots can cost between $6,860 to $13,710.

Nanjing Silicon Intelligence (NSI) has access to Huawei’s Pangu large language model and aims to pair digital avatars with LLM datasets to enable digital immortality as entertainment. Co-founder of the NSI, Sun Kai, created the video-enable chatbot platform for the bereaved to communicate with their lost loved ones. China’s AI regulations have specific rules for deepfakes and require the person whose personal information is being used to create a deepfake to be notified and give content. How this is regulated is not certain.

To address these concerns, the UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional has compiled a Safer Chatbots Implementation Guide for the region which is experiencing a substation uptake in chatbots as substitutes for mental health care practitioners. North America is dominating the mental health chatbot market and therapy sector, with wellness initiatives addressing gaps in the mental health care system.

Ray Kurzweil edges further to singularity

The future of griefbot technology is being pioneered by futurist and inventor Ray Kurzweil who predicted that people will be able to connect their brains to machines, known as singularity, by 2045. He lost his father when he was 22 and is creating a replicant of his late father by feeding an AI system with his letters, essays, and musical compositions. More ambitious plans include using nanotechnology and DNA from his father’s bones. Of course, Kurzweil will have to dig the bones up first which seems like a lot of effort. The ‘Dad Bot’ would be able to converse with Kurzweil about his work. Writing from personal experience, I think this moving dangerously close to prolonged grief. If we are forever stuck in our deceased loved ones’ past lives, how will we live and enjoy our lives?

Amit Roy-Chowdhury, a Professor of computer engineering at the University of California, Riverside, doesn’t think we are close to recreating AI replicas of the dead that could fool the living.

All artificial intelligence uses algorithms that need to be trained on large datasets. If you have lots of text or voice recordings from a person to train the algorithms, it’s very doable to create a chatbot that responds similarly to the real person. The challenges arise in unstructured environments, where the program has to respond to situations it hasn’t encountered before. Many of these AI systems are essentially just memorizing routines. They are not getting a semantic understanding that would allow them to generate entirely novel, yet reasonable, responses.

When we learn about some very sophisticated use of AI to copy a real person, such as in the documentary about Anthony Bourdain, we tend to extrapolate from that situation that AI is much better than it really is. They were only able to do that with Bourdain because there are so many recordings of him in a variety of situations. If you can record data, you can use it to train an AI, and it will behave along the parameters it has learned. But it can’t respond to more occasional or unique occurrences. Humans have an understanding of the broader semantics and are able to produce entirely new responses and reactions. We know the semantic machinery is messy.

In the future, we will probably be able to design AI that responds in a human-like way to new situations, but we don’t know how long this will take. These debates are happening now in the AI community. There are some who think it will take 50-plus years, and others think we are closer.

This yearning and aching we feel when someone close to us dies can be crippling. Isn’t it a kind of madness to dig up graves to harvest DNA to recreate our deceased, which Kurzweil is suggesting? All that time and energy when we have so little time on this earth. When will we say, enough is enough, they lived and they died? I want to live.

Ginger Liu is the founder of Hollywood’s Ginger Media & Entertainment, a Ph.D. Researcher in artificial intelligence and visual arts media — specifically grief tech, digital afterlife, AI, death and mourning practices, AI and photography, biometrics, security, and policy, and an author, writer, artist photographer, and filmmaker. Listen to the Podcast — The Digital Afterlife of Grief.