And the death tech startups recreating the dead

I’m a practice researcher in the visual arts and I’m studying death tech platforms, specifically how grief tech is designed to communicate with the bereaved on various platforms and applications. Can artificial technology do two things? One is the ability to support the grieving or hinder the process. Secondly, can AI represent the essence of who we are in a similar way as portrait photography, and if so, does AI replace photography’s 150-year reign as an identity referent and vessel of memory?

The development of AI technology raises significant ethical concerns about grief and mourning. The implications of creating AI avatars for the deceased without permission is a legal and moral issue that some death tech companies have addressed in their terms and conditions.

Beyond current limitations, the advancement of AI technology suggests that avatars will improve over time and will be more realistic and personalized. Although this sounds like a positive step in preserving the memory of our dead loved ones, prolonged grief could be a debilitating outcome if the dead are recreated in exact detail.

Other ethical considerations are at play. Who owns the avatar after the individual’s death and how secure is their data? What happens if an avatar that is shared between family members ends up on the internet and is shared by strangers? Would you want your parent’s likeness to be repurposed as new content by a third party? Yet, the same thing could and does happen to our tangible objects after we die. Markets are full of old discarded photographs of long-lost families.

There’s no legal defense about these photographs being used by third parties. Unknown family memorabilia for sale on market stalls is pretty much the same as digital and AI images lost on the internet, it’s just a different technology that creates, produces, and shares images. But while the family is alive, the potential psychological impact on the bereaved interacting with AI personas or replicas of their dead loved ones raises important ethical questions with few answers because the technology is so new.

Death Tech Startups

Hereafter AI

In 2016 James Vlahos faced the reality of his father’s terminal lung cancer. Wanting to save his father’s memories, Vlahos recorded his life story, hoping to preserve his precious memories but he needed something that captured more of the essence of his late father. Vlahos spent nearly a year programming an AI-powered chatbot replica of his father, which he named Dadbot.

Vlahos’ Dadbot experience inspired him to found the company, HereAfter AI, a service that transforms uploaded memories into life story avatars where friends and family can communicate with their dead loved ones. It works by uploading the digital archives of the deceased, like emails, text messages, and audio, to create a digital version.

HereAfter AI is an interactive memory app that is designed to recreate the personality of the deceased by asking a series of questions and answers which creates a chatbot for the bereaved to interact with on their smartphone or cloud-based voice AI like Amazon’s Alexa. The audio chatbot is designed to engage with the bereaved by giving verbal responses to questions through stories and anecdotes.

Naturally, I tested out the app after spending hours setting up and recording my answers to a list of questions. As well as recording stories about my life, it prompted me to record “Sorry, I didn’t understand that. You can try asking another way, or move onto another topic…” and “sure,” all phrases I would never say. You can read how I got on with the setup here.

The integration of powerful AI chatbots like ChatGPT has accelerated the development of grief tech, leading to projects that live forever in the metaverse. HereAfter AI aims to enhance its conversational abilities using language models like ChatGPT to create a more interactive experience, while still ensuring that the AI communicates the information provided.

StoryFile

StoryFile generated a lot of publicity last year when it hired actor William Shatner to promote its death tech service. Of course, the actor is still alive and who better than him to answer questions about his rich and illustrious life, especially on the back of his recent journey into space?

StoryFile records audio and video footage of individuals before their death, creating an interactive video avatar that can attend their own funeral or be shared with descendants.

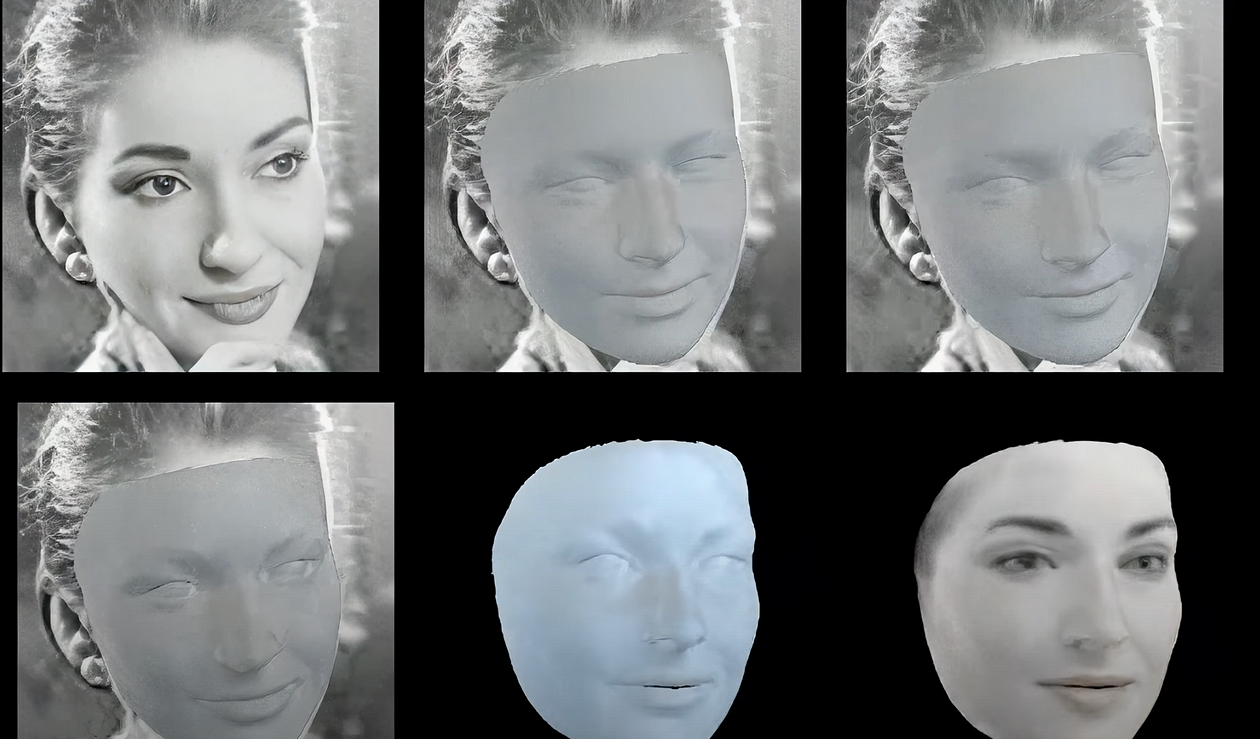

StoryFile’s founder, Stephen Smith describes the service as the virtual reproduction of the deceased which is programmed to deliver pre-recorded content in a way that closely resembles the real-life responses of the soon-to-be departed. However, there are limitations because the reproduction can only address topics within a predefined set of discussion areas. Smith’s team is developing the technology further to enable conversations with a 3D likeness of the deceased.

For the question-and-answer sessions, StoryFile uses an AI chatbot as the interviewer and it covers a range of topics. Smith, who previously led the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation, has been impressed by the AI’s capabilities, saying that ChatGPT can handle the task of an experienced oral historian.

What sets StoryFile apart from other death tech startups is that it doesn’t want to create AI for generating original spoken content, which some find unsettling. Smith favors a more natural approach. But other death tech founders like Justin Harrison, defend the use of AI technology in generating new content through natural language processing and generative AI.

The mental health implications of death and grief technology are under scrutiny. Smith acknowledges that some may find it too early to interact with a virtual reproduction of a loved one immediately after their passing. However, he believes that StoryFile provides a vital platform for preserving the legacy of the deceased for future generations.

Re;memory

Re;memory is developed by the Korean company Deepbrain AI, which is primarily known for creating interactive screens and AI news anchors. For $10,000 and a few hours in a studio, users can create a personal avatar to give to their family after they die. The AI is inspired by the Korean mourning tradition of Jesa, when family members of the deceased make annual visits to the resting place of their dead loved ones. Re;memory does not replicate the personality or essence of the deceased because the training data is limited to a single mood characteristic.

You, Only Virtual

You, Only Virtual take a different approach to communicating with the deceased. The company collaborates with clinical psychologists and offers additional mental health resources on its website, to encourage responsible usage of its technology and safeguard the well-being of its users.

You, Only Virtual focuses on the communication between a living person and the deceased, with an emphasis on recreating their personal one-on-one relationship. Its founder, Justin Harrison created the death tech company to redefine how people deal with grief. The app scans text and phone call messages to create data for a chatbot that can deliver original responses through text chats or audio and replicates the deceased relative’s voice.

Despite concerns about privacy and using personal correspondence without the deceased’s consent, Harrison argues that the user of the chatbot is the same person that the communications were initially sent to, thereby justifying its use.

Seance AI

Seance AI is described as a temporary emotional processing tool, which uses a pay-per-session model rather than encouraging long-term digital connections. Leading the development of Seance AI is designer Jarred Rocks who wants users of the platform to not experience it as a permanent connection with the deceased, but rather to provide users with a channel for closure. The AI tool sets up a brief exchange that lets users express themselves in ways that perhaps were unavailable before, like after a sudden death. I gave it a try here.

As AI tools improve, the authenticity of griefbots will likely become more convincing, raising questions about whether they truly facilitate bereavement or mess with our sense of reality and our mental health.

How We Grieve in the Digital Age

The digital age has made coping with loss more complex as the digital ghosts of people remain on social media posts and elsewhere on the internet. Some find solace in revisiting online archives of their lost loved ones, especially on Facebook memorial sites but the content of these profiles is stuck firmly in the past.

While the idea of connecting with deceased loved ones through AI avatar chatbots may bring comfort, it also raises ethical and psychological questions. Preserving memories and passing along family belongings has been a constant throughout history, prompting tech companies to explore new ways to support this process.

The application of avatar chatbots is not solely limited to coping with grief and loss. It could also serve as a tool for documenting personal thoughts, communicating difficult conversations, and preserving memories in the present. Such avatars may have value and purpose even when people are alive, allowing them to pass down their experiences to future generations.

While avatar chatbots can be beneficial during the grieving process, they also raise concerns about their impact on mental health and emotional well-being. Some research indicates that excessive reliance on avatar chatbots might hinder their ability to adapt to loss and prolong grief.

Death tech designers still face significant challenges in accurately mimicking a deceased person while dealing with issues of privacy and consent. Generative AI tools like ChatGPT string words together based on statistical probability, and have been known to produce arbitrary, false, or harmful content.

New York University professor, Gary Marcus warns that systems like ChatGPT can’t accurately replicate a relative, as they tend to fabricate information. But advancements in audio and video reproduction have made digital copies of deceased individuals possible, making technology like deepfakes, more accessible.

Marcus believes that generating AI’s arbitrary or inaccurate responses may pose risks to users. He emphasizes the need for a clear understanding of the technology’s limitations, as these models can more convincingly mimic human behavior.

How do we check the authenticity of the words spoken by an AI persona? In the case of grief tech, authenticity is about being as close as possible to how the deceased looked and sounded. This depends on the volume of data entered into the chatbot. Even with vast amounts of training data, the chatbot might still provide inaccurate information. Responding to complex questions remains a struggle for these chatbots, as they lack the point of view and essence of the deceased.

While challenges remain, advancements in AI technology are bringing us closer to lifelike virtual interactions with departed loved ones. However, the ethical implications surrounding privacy and consent must be carefully addressed as these technologies continue to evolve.

Replicating the Birth of Photography

The recent emergence of AI grief tech presents a unique take on family remembrance which echoes the new techno craze of photography on its emergence in the 19th century. Photography captured the Victorian’s imagination and it is no wonder that despite some initial flaws in its invention, the technology evolved at a rapid pace, from capturing the essence of the elite to memorializing the family in life and in death.

It’s an exciting time and I say that even as a photographer who has battled and embraced analog, digital, and now AI. Photography didn’t replace painting in the 19th century, in fact, it led to artists creating a new vision of the world rather than replicating it in exactitude. Photography has evolved from large format to instant cameras, from analog to digital. The reasons why we take photographs of our loved ones haven’t changed in 150 years but the technology has. AI is used to edit and enhance photographs but this isn’t the AI we are talking about here.

A year ago I wrote about the similarities of the photography and AI revolution and I discussed the history of taking photographs to create our likeness and to preserve memories. Photographs, films, and videos of our loved ones capture a moment in time. AI has the ability to do something that radically shifts memory, time, death, and identity.

Those of us who have lost loved ones understand the connection we have with the objects and memories left behind. Many of us talk to the photographs of our lost loved ones or blow a kiss to their image, as I have done on many mornings.

The evolution of technology has shaped the way we grieve, from the early days of photography, which brought images of our loved ones into our homes, to Facebook Memorial pages that serve as spaces for remembrance. Incorporating AI into the grieving process seems like a natural progression. Adding a layer of interaction can be comforting, especially during the initial stages of loss. For those who missed a chance to say goodbye, griefbots can offer closure.

As we jump into an AI-driven future, the stories, memories, and voices of the past continue to resonate within the algorithms of our digital world. Whatever technology we use, ultimately the essence of human connection and the significance of genuine memories remain central to human agency.

Ginger Liu is the founder of Hollywood’s Ginger Media & Entertainment, a Ph.D. Researcher in artificial intelligence and visual arts media — specifically grief tech, digital afterlife, AI, death and mourning practices, AI and photography, biometrics, security, and policy, and an author, writer, artist photographer, and filmmaker. Listen to the Podcast — The Digital Afterlife of Grief.